swissfillon is a young, fast-growing company based in Visp (Switzerland) that offers aseptic drug product manufacturing (filling) services for complex, high-value injectables that require specialist capabilities and expertise. Its innovative, fully automated and flexible filling line is suitable for vials, syringes and cartridges in batch sizes of 1–200 L.

KSR: Almost immediately after you started operations, the pharmaceutical industry was transformed by the need to develop a COVID-19 vaccine and deliver hundreds of millions of doses in record time. What impact has this had on your business model and could the remarkable achievements of companies working together during the pandemic usher in a new era of collaboration?

DK: As everybody is aware, there is a lack of fill-and-finish drug product manufacturing capacity because of the enormous requirement for COVID vaccines. At the same time, the move away from a silo mentality is making it a great time to be a CMO. We strongly believe in forming partnerships throughout the entire value chain.

Daniel Kehl

Our view is that the world is getting more complex and companies should not aim to do everything by themselves. We can add more value to our customer offering if we collaborate to develop tailor-made solutions that meet their specific needs and requirements. For example, we have established close partnerships with secondary packagers to fulfil specific requests for the ophthalmic market.

CD: Many countries have realised that there are risks associated with outsourcing therapeutics manufacturing overseas; as such, we have been involved in discussions with the Swiss government to look at sourcing critical production and fill-and-finish activities here in the heart of Europe.

Small CMOs like us now have greater opportunities to offer our services to everybody who needs them. We are also getting enquiries from companies who, because of the uncertainty surrounding Brexit, prefer not to collaborate with UK companies at present.

We have approximately 50 employees, all based at the same facility, so we didn’t have the option of switching to other sites during lockdown; luckily, though, our production was not affected.

My personal philosophy is that you learn most not by success … but by overcoming challenges; so, from that point of view, we are really living through interesting times.

Carole Delauney

KSR: We’re reading a lot about neoantigen-derived vaccines and oligonucleotide drugs at the moment, and it strikes me that the ongoing rise of biologics could put your company in a very strong position.

DK: For early stage companies looking to initiate Phase I manufacturing, there’s currently a lack of capacity. Plus, with CMOs focussing on COVID vaccines, there’s a danger that small R&D programmes could come to a halt or fail.

As a result, many companies are very keen to initiate collaborations with us to provide material for their clinical phases; and, for this kind of requirement, I really think that that we are an ideal partner. We are fast, we are agile, we can provide a broad variety of technologies and have the ability to fill a wide range of different containers.

But, the requirement of companies developing COVID vaccines is to produce hundreds of millions of doses and, from a capacity — but not a technical — point of view, we are currently too small to provide these quantities.

From the very beginning of their journey to commercial production, our aim is to be a service provider for the entire lifecycle of our customers’ projects.

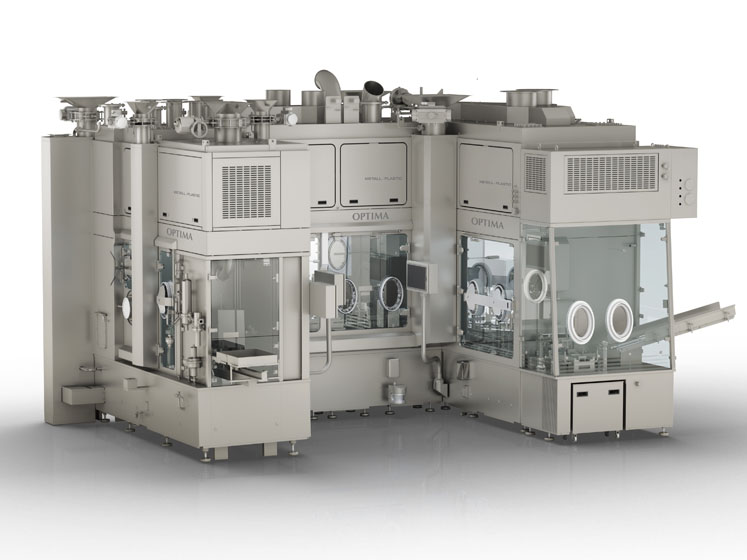

So, our strategy is clear: we started with a highly flexible, fully automated fill-and-finish line providing small to midsize quantities (mainly for clinical phases) and, last year, we initiated an investment programme that will allow us to build a new line to produce larger commercial quantities for our current and future customers.

We will be starting engineering work this year and aim to have the facility up and running for high volume vaccine manufacturing by mid-2024.

KSR: It seems likely that there could be future pandemics and we will need vaccines for different viruses if they jump (again) from animals to humans. How is your pipeline for small-stage R&D and is there a threat that digital clinical trials and molecular modelling may lessen the requirement for early phase production?

DK: Our original aim was to provide a solution for small to mid-size products and for highly complex ones that have been getting more difficult to produce and fill.

We wanted to provide that service because what we heard, and what we are still hearing, is that the big players are not interested in filling 10,000 to 20,000 units; but, if this capability isn’t available, these companies can’t get started.

Today, there is even less interest in supporting new products. This might force some companies to consider digital options to analyse their proteins or molecules without doing GMP testing or clinical trials.

But, I suspect that the human body is so complex that we’re not yet at the stage of being able to use virtual simulations. Also, it’s probably fair to say that the regulatory authorities are quite conservative and the day when they’d accept a simulated clinical trial that doesn’t involve humans is some way off.

With the move towards personalised medicine, pharmaceutical companies have begun to realise that every person reacts a little differently to the same or similar active ingredients.

This makes it more difficult to justify computer simulations to bypass clinical studies on human beings. By contrast, if you just look at genome sequencing, for example, it’s clear that science is advancing at remarkable speed and many processes will inevitably evolve and improve.

KSR: As more and more drugs are being formulated as liquid forms, do you think there will be a move away from solid dosage? And, are there further applications for fill-and-finish drugs that will maybe go beyond pharma into the nutraceutical space?

CD: I think there is valid justification for different application forms. A few years ago, there was debate around whether, in the future, everything could be applied orally with, say, intelligent encapsulation.

Maybe some of today’s injectable drugs could be applied orally, but there are many different therapies that I’m sure will continue to require either subcutaneous or intravenous injection.

Another trend has been towards lyophilisation, which is a complicated technology. There was a recent push for companies to develop stable liquid forms but, today, large numbers of new products are entering the market that need lyophilisation.

I think these different technologies and applications go in parallel. It’s hard to see that one technology will take over, but there are certainly examples of new techniques completely replacing something that was used for many years.

KSR: By streamlining the drug production process and moving towards a lifecycle support approach, could we reduce the cost per patient and make the genius of the pharmaceutical industry available to more people?

DK: Cell and gene therapies represent the start of a new era and a huge amount of research effort is focused on reducing costs to make them more widely available. The industry is making amazing advances, but this does raise questions in terms of what is affordable for society and what is ethical in view of the enormous cost per patient.

Our role is to lower prices, particularly with injectable solutions that can be self-administered by patients. This can have a significant impact in terms of lowering the cost per patient as healthcare professionals are no longer needed to administer the drugs; and, of course, it also makes life easier for the patient.

For us as a fill-and-finisher, it’s an additional challenge to provide workable solutions for wearable devices, pen applications, autoinjectors and so on, but we strongly believe that we can provide solutions that will reduce the financial burden.

We can also look at more automated filling lines, which speed up the time from production to final release. If we can implement automated solutions to control the quality of the filled container, there is a significant time advantage as well as a cost saving.

KSR: So much of what you've just talked about has been accelerated as a result of the pandemic. Potential innovations have been forced to the foreground and are beginning to be implemented.

CD: Absolutely. For example, almost everybody has a smartphone and there are many health applications — such as virtual clinical trials and remote monitoring — that would decrease costs and improve patients’ lives.

We always try to think ahead and embrace the latest innovations. In the new normal, we have to challenge ourselves to provide the best solutions and to crystallise the unique selling propositions that we can offer. Perhaps, because we are a young organisation, we are in a great position to embrace these opportunities and rapidly implement them into our company.

KSR: For now and the future, how can you work with your customers to maximise the benefits that you offer?

DK: There is still a perception amongst drug substance manufacturers that fill-and-finish is simple and straightforward. In this area, though, we are probably the most agile company in the world.

We can switch from one product one day to another the next; today we can fill vials and tomorrow we can fill syringes. We have purposely designed everything that is in direct contact with the drug product with single-use, dedicated components to ensure speed and agility.

Of course, if we have delays in getting these components, we lose this advantage. We can’t simply order filters, for example, and hope that one in particular will work for every product … and there is sometimes a lack of understanding among our customers regarding how complex our requirements are.

During the pandemic, we have seen lead times for some single-use components increase from around 12 to 50 weeks. In the past, a company had to contact us at least 8 months in advance of getting a product on the filling line, and now it’s even longer.

We are trying our best to evaluate exactly what is needed in terms of primary component starting materials and are implementing a strategy aimed at maintaining maximum agility; but, if we could get one message to our customers, it would be to speak to us at the earliest possible stage so that we can plan ahead.

It’s a new world and companies involved in more innovative technologies tend to be more likely to consider manufacturing requirements from the very beginning of their journey.

This can make a huge difference in terms of their speed to market. You may have a great molecule, but you need to be able to sell it in a suitable form, so you have to find somebody to produce the API, formulate the drug substance and deliver it in a suitable container. Taking a lifecycle approach is the key to success.