Even when they quietly touch hundreds of thousands of patients across continents, they can still be defined as “rare” by regulatory bodies (fewer than 200,000 in the US and roughly one in 2000 people in Europe).

Collectively, these genetically driven, often severe conditions span every therapeutic area — from oncology and neurology to immunology and metabolic disease.

This creates a patient population measured not in millions for any single therapy, but in significant unmet need across millions of lives.

Serving this fragmented global community demands a different pharmaceutical model: one built not on scale alone but on precision, integration and geographic reach.

These are the very capabilities that define the modern CDMO industry, which, at its best, is equipped to take these highly specialised molecules from early phase clinical trials to commercial reality.

David O’Connell, Director of Scientific and Technical Affairs at PCI Pharma Services, reports.

Precision molecules for precision populations

Rare diseases demand precision … and the molecules designed to treat them reflect that.

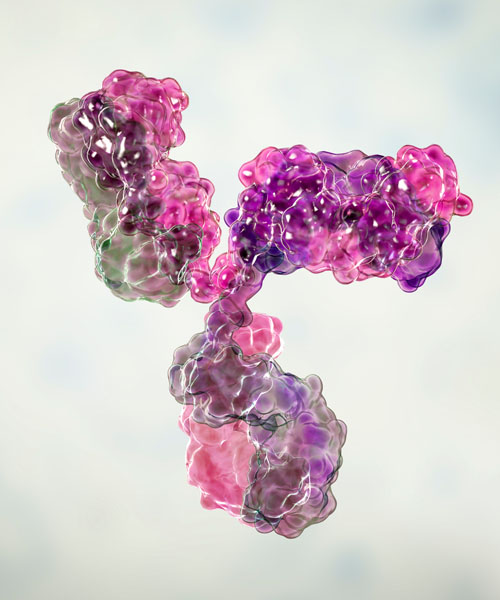

Unlike therapies for more common conditions, which often rely on well-understood molecules with broad applicability, many rare-disease programmes hinge on highly targeted agents that are tailored to distinct genetic or molecular signatures.

A substantial portion of modern rare-disease and targeted therapies are highly potent compounds, reflecting the broader industry trend wherein HPAPIs represent roughly 30% of drug development pipelines and are central to precision medicine approaches.1

It isn’t unusual for rare disease pipelines to be dominated by biologics, gene-based modalities or other specialised molecular classes, precisely because traditional “one-size-fits-all” drugs cannot address the underlying pathology of these conditions.

The biology of a rare disease is itself precise: roughly 80% of them have a genetic component, making them amenable to molecularly directed approaches such as antisense oligonucleotides, enzyme replacements or targeted inhibitors that modulate specific pathways or proteins.2

These modalities often require sophisticated formulation, containment and dose control far beyond standard therapies.

At the same time, the industry’s broader research focus is shifting accordingly: industry analyses suggest that roughly 35% of all drugs and biologics in global R&D pipelines are aimed at rare diseases.3

For developers and their manufacturing partners, this molecular precision translates into complexity: APIs that are potentially highly potent, bespoke biologic processes and the need to balance stability, safety and efficacy in tiny patient populations.

It’s a landscape in which scientific nuance is inseparable from operational execution.

Structural considerations for rare disease programmes

Rare disease drug development does not simply operate at a smaller scale; it operates under a different set of physical, regulatory and human constraints.

There are more than 7000 recognised rare diseases worldwide, collectively affecting an estimated 300 million people.4 Yet, fewer than 5% of these conditions have an FDA-approved treatment.5

In conventional pharma, large patient populations allow for trial delays, formulation iterations and wide-scale manufacturing tolerances.

In a rare disease, they do not. A single trial site may represent a significant proportion of the available patient pool … and missing a shipment can meaningfully delay or derail a study.

Clinical trial enrolment itself is a structural challenge: rare disease studies enrol significantly fewer participants than common disease trials and many rare diseases have seen fewer than 10 trials conducted overall.

Patients are typically scattered across multiple regions, compelling sponsors to navigate multijurisdictional regulatory frameworks and logistics for very small volumes.

Meanwhile, therapies often involve highly potent, targeted molecules or genetically informed modalities, demanding precision in formulation and delivery. In this environment, fragmentation is a risk.

Successful rare disease development requires the orchestration of science and supply, delivered by a model shaped around agility, adaptability and global reach rather than scale alone.

Integration matters

The central challenge is not how much medicine can be produced, but how precisely it can be made, released and delivered.

Volumes are often measured in hundreds or even dozens of units, yet those units must reach patients dispersed across multiple countries, under tightly controlled regulatory and quality frameworks.

A single clinical or commercial batch may represent a meaningful share of the global supply, leaving no room for deviation in formulation, sterility or containment.

This reality places unusual demands on manufacturing infrastructure. CDMOs supporting rare diseases must be capable of low-volume, high-mix (LVHM) production, whereby frequent changeovers, short campaigns and evolving formulations are the norm rather than the exception.

For many rare disease therapies, including highly potent small molecules and sterile injectables, this must be delivered within advanced containment systems designed to protect both product integrity and operator safety — often at exposure limits measured in micrograms.

At the same time, those small batches must be packaged, labelled, released and distributed into a multiregional clinical and commercial supply network, supporting trials and patients across North America, Europe and beyond.

This is when integration becomes decisive. When development, oral solid dose and sterile manufacturing, quality and global distribution sit within a single CDMO framework, rare disease sponsors gain something more valuable than scale: continuity of control from first patient to last dose.

From FIH to commercial supply

Consider a theoretical rare-disease therapy entering first-in-human trials with fewer than 20 patients worldwide. The biology is highly specific, the therapeutic window is narrow and the doses are measured in micrograms rather than milligrams.

For both patients and the drug's sponsor, this creates a set of demands that are fundamentally different from those in conventional pharma. The programme must accommodate

- a globally dispersed patient population requiring clinical supply into multiple regions from the very first study

- extremely small cohort sizes wherein each dose and each batch carry outsized importance

- possibly a highly potent, targeted active ingredient, demanding advanced containment and precise dose control

- a compressed development pathway in which early pharmacokinetic and safety data must be generated quickly to avoid losing scarce patient enrolment

- a need for ultra-low-dose first-in-human material, often enabled through microdosing platforms such as Xcelodose.

Meeting these demands requires a manufacturing and supply infrastructure that’s built for precision rather than volume.

Early clinical material is produced using controlled microdosing systems that deliver uniformity at the microgram level, protecting patients while generating reliable data.

As the programme progresses, the same formulation and containment strategies are carried forward into larger batches, preserving continuity and avoiding disruptive redevelopment.

At the same time, clinical trial supply becomes a global exercise: packaging, multilingual labelling, regulatory release and distribution into regional depots must all be co-ordinated for very small, high-value shipments.

Digital supply platforms track site-level demand and inventory in real-time, ensuring that no patient misses a dose because of forecasting errors or logistical delays.

By the time the therapy reaches late-stage development, the operational framework supporting it is already aligned for commercial reality.

The infrastructure that makes rare disease medicine possible

Rare disease medicine now sits at the intersection of scientific possibility and industrial responsibility. The tools to design targeted therapies exist and the pipelines are increasingly rich with orphan and precision assets.

What determines whether these advances translate into real outcomes for patients is no longer discovery alone, but the infrastructure that surrounds it.

Rare diseases expose the limits of pharmaceutical models built around volume and scale and replace them with different priorities: precision, continuity and global co-ordination.

Success depends on moving seamlessly from laboratory insight to manufacturable product, from early clinical material to long-term commercial supply, and from fragmented efforts to integrated operational systems.

For patients, this infrastructure is largely invisible. What they experience is simply whether a therapy exists and whether it continues to be available.

Behind that sits a complex machinery of formulation science, containment engineering, regulatory alignment and global distribution, all of which are designed to serve populations too small to benefit from mass-market logic.

In that sense, rarity is no longer just a biological category. It is a measure of how willing the industry is to build systems for those who cannot be served by scale.

Not because it is easy, but because the science, the infrastructure and the ethical imperative have converged.

References

- www.pharmiweb.com/press-release/2025-05-15/global-hpapi-market-key-growth-drivers-9-cagr-and-trends-shaping-the-industry-by-2029.

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12658154/.

- www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/the-hard-truth-about-rare-disease-and-gene-therapy-drug-development.

- www.who.int/news/item/24-05-2025-seventy-eighth-world-health-assembly---daily-update--24-may-2025.

- www.ohe.org/insights/advancing-rare-disease-care-challenges-and-key-issues/.